The law of praying (8): Looking up to heaven and back in time

We are looking at a section from the Canon of the Mass each week, to learn what the ‘law of praying’ has to teach us about what we believe. You can find the previous posts in this series in our reflections archive.

Therefore, O Lord,

as we celebrate the memorial of the blessed Passion,

the Resurrection from the dead,

and the glorious Ascension into heaven

of Christ, your Son, our Lord,

we, your servants and your holy people,

offer to your glorious majesty

from the gifts that you have given us,

this pure victim,

this holy victim,

this spotless victim,

the holy Bread of eternal life

and the Chalice of everlasting salvation.

As we saw from the consecration, the Mass makes Christ’s Passion and Death present through the apparent separation of his Body and his Blood. But the Mass is more than a symbol. Christ is in heaven. Wherever he is, that place becomes heaven. Now that he is on the altar, it is as if we too stand with him in heaven. And we see history from God’s perspective. All of time is present to us. And so not only do we have a symbol of the Crucifixion before us, but we are, ourselves, present at the foot of the Cross, through this mystery. We are present at all those events throughout time, but especially those most important events in the history of our salvation. And we are present at the empty tomb as Christ rises from the dead. We are there watching Christ ascend into heaven.

We speak of Christ as a ‘victim’ here not as we hear it used by the police, but in its original sense of a sacrificial animal. Which prepares us to recall those sacrifices in the Old Testament that have foreshadowed Christ’s own sacrifice.

Be pleased to look upon these offerings

with a serene and kindly countenance,

and to accept them,

as once you were pleased to accept

the gifts of your servant Abel the just,

the sacrifice of Abraham, our father in faith,

and the offering of your high priest Melchizedek,

a holy sacrifice, a spotless victim.

Three sacrifices are mentioned, but not those ordered in the Law of Moses, like the Passover lamb. All three are found in Genesis, at the very beginning of salvation history. Which shows us that, from the very beginning, God knew what he would do to save us, and was already helping us to understand Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross.

Cain and Abel both offered sacrifices to God. Cain offered ‘fruit of the earth’, while Abel sacrificed lambs. Abel offered a sacrifice acceptable to God where his brother Cain did not. What made his sacrifice acceptable was not God’s dislike for vegetarians, but the spirit in which each brother made his sacrifice. Abel was just, but Cain revealed the evil inside him when he gave into jealousy and murdered his brother. And so Abel gave us that first hint of a just man who offered a perfect sacrifice, and who would be killed for no reason other than that his spirit was perfectly united to God (Genesis 4).

Abraham was asked to sacrifice his son Isaac (Genesis 22). ‘Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love,’ he was told, preparing us for another Son, only begotten and beloved of his Father, who would also climb a mountain to offer himself in sacrifice, carrying on his own back the wood he was to be sacrificed on. God stopped Abraham from killing Isaac, but we are told that it was because of his faith in God’s power to give life even to the dead that he was willing to do so (Hebrews 11). Christ’s willingness to give himself entirely to God surpasses the obedience even of Abraham and his son Isaac. And it is through his obedience that God’s ability to give life to the dead was demonstrated.

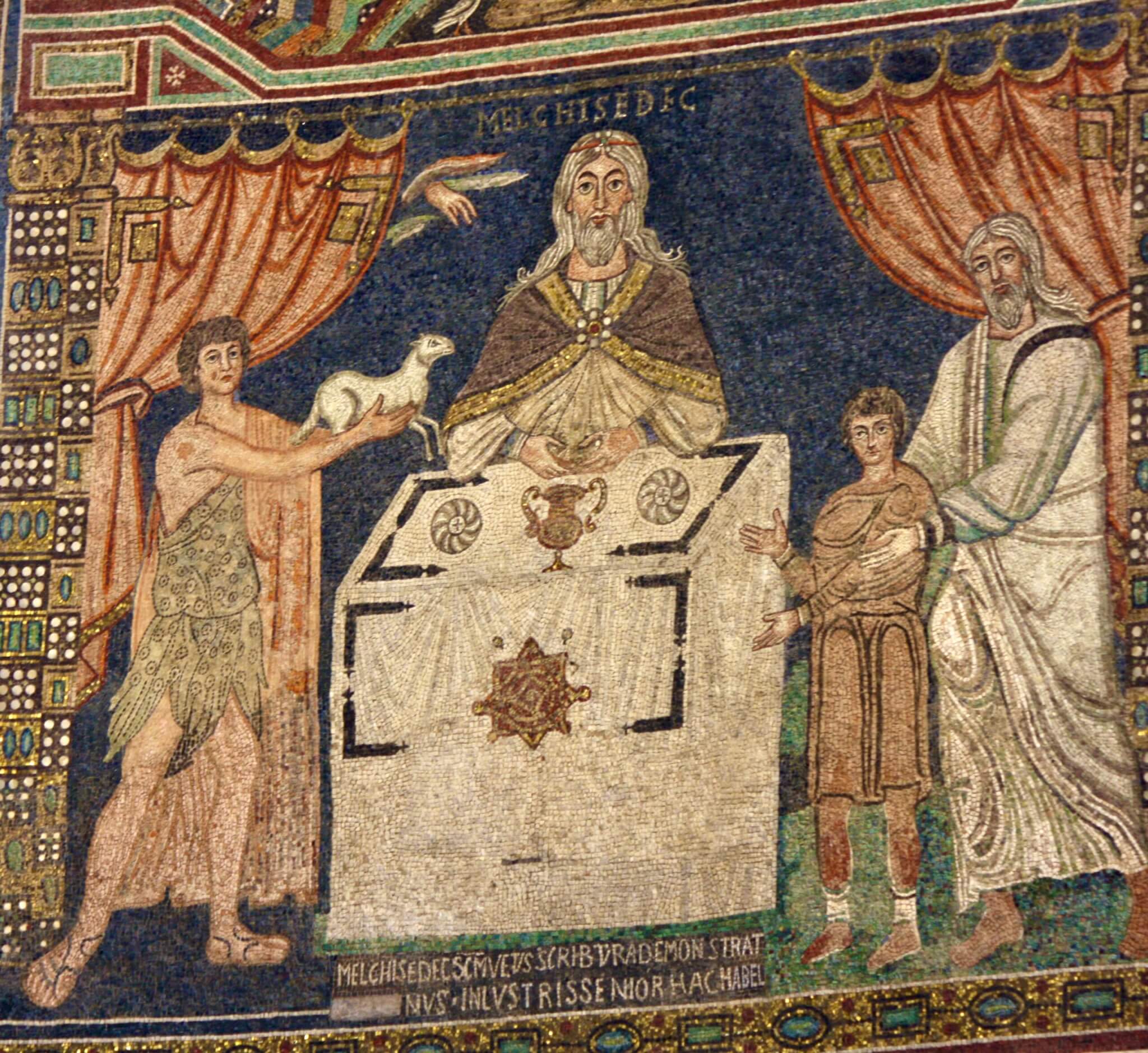

Abel and Abraham are some of the better known figures from the scriptures. But Melchizedek is not often spoken about. And that might be because he generally creates more questions than he answers.

Melchizedek appears without any introduction. Abraham is on his way home after winning a great military victory. Melchizedek offers a sacrifice and blesses Abraham, so Abraham gives him a tenth of everything he won in battle. But that creates a mystery. ’It is beyond dispute that the inferior is blessed by the superior’ (Hebrews 7:7), so who could this figure be, who is greater than Abraham? No one is greater than Abraham, surely? And why does Abraham give him a tithe of his goods — the priestly portion?

Melchizedek then disappears from scripture as quickly as he appeared, until a brief mention in Psalm 109, where the Lord swears an oath to the Messiah: ‘You are a priest forever, according to the order of Melchizedek.’ For the first time, Melchizedek’s eternal priesthood is linked to the Messiah. And then, once again, Melchizedek disappears… until the New Testament. Finally, all is unpacked and explained for us in Hebrews.

‘He is first, by translation of his name, king of righteousness, and then he is also king of Salem, that is, king of peace.’ (Hebrews 7:2) Can we think of another king of righteousness, a prince of peace, who is also a high priest, who offers sacrifice in Salem (known later as Jerusalem)? Everyone in Genesis is introduced by some kind of genealogy or description of his parents. But Melchizedek is not. ‘He is without father or mother or genealogy,’ Hebrews tells us and therefore ‘has neither beginning of days nor end of life.’ Can we think of a kingly, high priest of peace and righteousness, born before all ages and whose kingdom will have no end, who offers sacrifice in Jerusalem?

All of this does, of course, point to Jesus, but so far this foreshadowing hasn’t taught us very much. Abraham met someone who foreshadowed Jesus. So what? The key is what he sacrificed.

‘And Melchizedek king of Salem brought out bread and wine; he was priest of God Most High.’ (Genesis 14:18)

Melchizedek doesn’t foreshadow Christ’s righteousness (as Abel) or his perfect obedience (as Abraham), but the means by which that sacrifice would be continued for the rest of time: under the forms of bread and wine. God had people looking forward for thousands of years in expectant hope of the great mysteries we now celebrate and can encounter every day.