St Aloysius' Day

We were pleased to welcome Fr Gerard Skinner, Parish Priest of St Francis', Notting Hill Gate and Dean of North Kensington, to preach at the High Mass last night for St Aloysius' Day. Here are his words:

The Vocation of St Aloysius Gonzaga

‘They have vanished’, wrote Aldous Huxley of the Gonzaga; ‘they are as wholly extinct as the dinosaur’. And yet here we are this evening, singing the praises of a Gonzaga. Of all the Gonzaga, it was to be one of the most short-lived who was to be granted the most impressive reign – not merely a reign of some span of years in this world but rather imperishably in aeternum.

The life of St Aloysius , familiar to many of you, may be told swiftly. He was born in 1568, the eldest son of Ferrante Gonzaga, marquis of Castiglione in Lombardy and a prince of the Holy Roman Empire. His mother was a member of the Della Rovere family and between his parents, Aloysius numbered as members of his family dukes, marquises, cardinals and bishops throughout Italy, Spain, France and Germany. From the age of seven he dedicated his life to prayer and mortification, channelling all the fighting energy and stubborn resolve for which his family was renowned, into practising his faith. At the age of twelve he received his First Holy Communion from the hands of St Charles Borromeo. After great opposition from his father who had expected his son to take up a military career, Aloysius renounced the marquisate of Castiglione in favour of his younger brother, and in 1585 entered the Society of Jesus’ novitiate in Rome. ‘I am a piece of twisted iron:’ he wrote, ‘I entered religion to get twisted straight.’

In the novitiate he had to be instructed to pray less and refrain from such vigorous mortifications as he had previously imposed on himself. He was noted for his oft repeated desire for an early death but this was more than matched by his eagerness to take on the most menial tasks possible in the novitiate such as sweeping the cobwebs off the ceiling.

In the early months of 1588 Aloysius was admitted to minor orders. The following year the plague broke out in Rome, the saint’s first biographer recording, ‘Verily it was a horrible thing to see the dying creeping to the Hospitals, stinking and loathsome, and sometimes to behold them giving up their last breaths in corners, or falling down dead at the foot of some pair of stairs.’ The Jesuits opened up a hospital for the plague victims and Aloysius asked to be allowed to serve there. He nursed and instructed them, begged for food for them throughout the city and saw some of his confreres die from the disease.

He continued to devote himself to God and the care of the sick until he succumbed to the disease himself, dying at the age of twenty-three with the Holy Name of Jesus on his lips. He was beatified just fourteen years later in 1605 by Pope St Pius V and canonized in 1726, being declared the patron saint of young students three years later and, in 1926, Pope Pius XI pronounced him the patron saint of all youth.

*

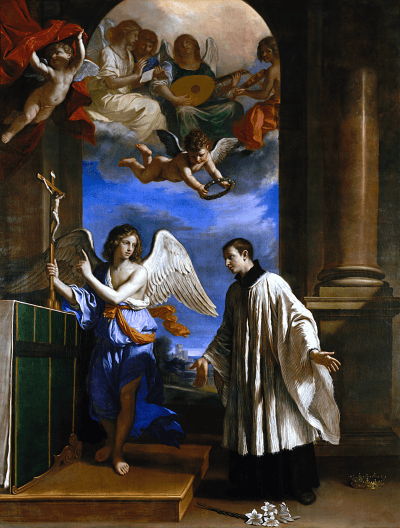

After his death, many paintings and statues of St Aloysius were created, one such painting, impressive not least for its size, now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It is a huge altarpiece by the Bolognese artist, Guercino. The work, entitled ‘The Vocation of St Aloysius Gonzaga’, was originally commissioned in 1650 for the Theatine church of Guastalla by Duke Ferrante III Gonzaga (1618–1678).

Guercino depicts St Aloysius much like contemporary portraits of him painted from life – slim face, long nose, like many of his family, but the saint is wearing a black Jesuit cassock and a voluminous white surplice. The moment depicted, in allegory, is that of St Aloysius’ decision to heed his heavenly call.

As we look at the painting it is as if we were standing at the side of a chapel, looking across the front of the altar to an arch, through which can be seen the countryside and the strikingly blue yet cloudy Italian sky. Guercino depicts St Aloysius standing, on the right of the picture, before the predella of the altar. Upon the predella stands an angel of similar height and stature to the saint. The angel is dressed in blue, an orange sash, around his middle. Above the two figures we can see more angels, one playing a lute, another a viol, two more singing from a manuscript.

Through the arch, in the midst of the countryside, we can see the family’s principal castle and, discarded by the Saint’s feet, is the coronet of the marquis. These symbolize St Aloysius’ renunciation of the worldly glory and power that was his birth-right. He had the courage to take a deliberate decision to follow his God given vocation. Despite the prolonged anger of his father and family who did all that they could to persuade him to remain with them, St Aloysius would not utter the words to God ‘I will not serve’, it was not better, thought he, “to reign in [Castiglione], than to serve in Heaven.” (Cf Milton Paradise Lost Book 1). He wanted to give his life to the Church, not his bones – he heard the call of Christ and his response was decisive, bold, iron-willed.

At the feet of St Aloysius lies a single lily stem with seven flower heads. Guercino’s image is that of a young man who is not seemingly given to holding flowers. The lily, of course, is the symbol of chastity, a virtue for which the saint is famed. He was particularly noted for the practice of custody of the eyes, hoping to avoid all sins against purity that he feared he might commit. Here St Aloysius reminds us that ‘Blest are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.’ Preaching at the canonisation of St Maria Goretti – another saint famed for her chastity – Pope Pius XII reflected that ‘Not all of us are expected to die a martyr’s death, but we are all called to the pursuit of Christian virtue. This demands strength of character . . . a constant, persistent, and relentless effort is asked of us right up to the moment of our death. This may be conceived as a slow, steady martyrdom which Christ urged upon us.’

All this being said, the crown and the castle and the lily are but props in this painting compared to the dominant subject – St Aloysius intently yet serenely contemplating the Altar Crucifix that the angel grips with one hand and points to with the other. The saint stands before the Cross, slightly leaning towards it, his hands wide open and apart as if he is awestruck by what he sees. Perhaps we are present at the moment he prays the Suscipe of St Ignatius – his lips seem to be moving – ‘Take, O Lord, and receive my entire liberty, my memory, my understanding and my whole will. All that I am and all that I possess, Thou hast given me: I surrender it all to Thee to be disposed of according to Thy will. Give me only Thy love and Thy grace; with these I will be rich enough and will desire nothing more.’

This central image of Guercino’s painting recalls the saint’s love and respect for the angels – one of St Aloysius’ few writings to survive is a meditation on the angels – those mighty spirits of praise and spiritual warfare, those messengers of God, one of whom has been given to each of us ‘to light and guard, to rule and guide’.

The image also recalls St Aloysius love of the Cross of Christ, central for him in prayer, particularly as he was dying, for he could strive in his sufferings to follow his Divine Master in His humility and sacrificial love.

St Aloysius’ short life in the novitiate was a blazing crucible of the life of God in Rome. Yet despite this, as he prepared to die, he wrote to his mother, ‘In return for my short and feeble labours, God is calling me to eternal rest; his voice from heaven invites me to the infinite bliss I have sought so languidly, and promises me this reward for the tears I have so seldom shed.’

*

Walking through the streets of this city, a month ago, I noticed these words engraved on a college clock tower: ‘It’s later than you think. . .’ An everyday phrase rendered more impressive by the quality of the fine carving in honey-coloured stone. On the adjacent face of the clock tower, more words were inscribed, again in English: ‘. . . But it’s never too late to start.’ There is some intended humour in these words – the clock’s bell strikes at two minutes past each hour – yet the statement seems to acquiesce in the idea that tomorrow will always come. These words reminded me of how we can all put off to another time answering the call of God. How far from the zeal and energy of the early Jesuit fathers such as St Francis Xavier who would have liked to, ‘go round the universities of Europe . . . crying out like a madman, riveting the attention of those with more learning than charity’, hoping to ‘stir most of them to meditate on spiritual realities, to listen actively to what God is saying to them. . . [to] forget their own desires, their human affairs, and give themselves over entirely to God’s will and his choice.’ So that, ‘They would cry out with all their heart: Lord, I am here! What do you want me to do?’ (From the letters of St Francis Xavier)

Aloysius knew the urgency of responding to God’s call for ‘Time, the subtle thief of youth,’ (Milton, Sonnet 7) is ever moving on. Some hearing these words this evening are called now to offer themselves to be priests, brothers or nuns – follow St Aloysius’ example! Some are called now as lay men and women to offer yourselves to this church’s evangelizing mission – follow St Aloysius’ example! Some of us are called now to follow with renewed conviction the example of St Aloysius in our prayer and our renunciation of our self-will to conform ourselves afresh to the will of the Lord – on this feast day, let us follow St Aloysius’ example.

One important detail of Guercino’s altarpiece have I, so far, left out: above the saint hovers a cherub ready to place on Aloysius’ head a different sort of crown from that which he had laid aside. It is the crown of sanctity, made of laurel leaves for victory and white flowers for purity, a very singular halo for a most singular saint.

But now I must leave my praises of your patron saint as we turn again to the Lord. Let St Aloysius speak the final words, his final words addressed to his mother. As he faced death he wrote to her of the fulfilment of his and her vocation, praying that ‘our parting will not be for long; we shall see each other again in heaven; we shall be united with our Saviour; there we shall praise him with heart and soul, sing of his mercies for ever, and enjoy eternal happiness.’ So may it be.