Sermon for the Immaculate Conception

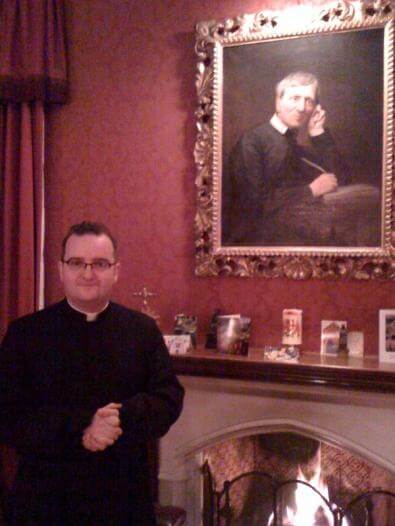

Fr Nicholas Schofield, Parish Priest of Uxbridge, Diocesan Archivist of Westminster and former Brother of the Secular Oratory (when he was an undergraduate at Exeter College) came to preach at the Solemn Mass for the Immaculate Conception. His sermon is reproduced below:

Rejoice, so highly favoured! The Lord is with you.

Whenever I come to Oxford, I try to make a short pilgrimage to the porch of the University Church of St Mary the Virgin. You all know it better than I - jutting out on to the High with its 'barley sugar columns', echoing Bernini's baldacchino in St Peter's, Rome. Built in 1637, I always think it offers a tantalising glimpse of the sort of architecture we might find across the country had there been no Protestant Reformation, had the English Baroque been Catholicised. The statue of Our Lady in the porch was actually used against Archbishop Laud at his trial in 1641, an example (it was thought) of his dangerous Romanising tendencies and such was the opposition the statue aroused that you can still see to this day the bullet-holes left by Cromwell's men.

That 'Virgin Porch' in the heart of this city seems to sum up the whole history of English devotion to Our Lady and, in particular, to the mystery of the Immaculate Conception, which we celebrate here tonight. Even though the statue dates from after the Reformation, its baroque splendour reminds us of this country's dignity as Mary's Dowry, a place where there had long been a devotion to the Immaculate Conception. In fact, one of the earliest mentions of a feast of Our Lady's Conception comes from an old Winchester Calendar, dating from around 1030. It seems that the Normans initially discontinued the Feast, for they tended to be suspicious of Anglo-Saxon observances. But then a Norman Abbot was saved from shipwreck after promising to establish the feast of the Conception and it henceforth became increasingly popular around the country.

If the magnificence of the 'Virgin Porch' reminds us of the English love for Our Lady, then the Cromwellian bullet-holes represent the story of turbulence and destruction, of shrines razed to the ground and images burnt. The Immaculate Conception was, of course, discarded as a corrupt superstition at the Reformation, though it is interesting to also remember that, not yet defined by the Church, the doctrine was vigorously debated in the medieval schools – including Oxford. One historian said that 'as England has the honour of having first celebrated the festival of Our Lady's Conception, so have her schools the credit of being the first to defend it scientifically.' Eadmer of Canterbury, for example, wrote a treatise in support of the doctrine and introduced the famous (though not entirely convincing) maxim: decuit, potuit, ergo fecit – in other words, the Immaculate Conception was possible, because nothing is impossible to God, and fitting, for how could the Mother of God not be Immaculate, therefore it came about, it was accomplished.

So, the Blessed Virgin has been debated by the schoolmen and rejected by the reformers, and yet in more recent times there has been something of a Marian revival. And part of this rediscovery was achieved by that scholarly-looking clergyman who would have been seen scuttling through the Virgin Porch and into the University church during the 1830s – as one of his disciples put it, 'walking fast, without any dignity of gait, but earnest, like one who had a purpose; yet so humble and self-forgetting in every portion of his external appearance, that you would not have thought him, at first sight, a man remarkable for anything'. His name: Blessed John Henry Newman.

Even as an Anglican, Newman had a strong devotion to Our Lady – 'in spite of my ingrained fears of Rome, and the decision of my reason and conscience against her usages', he wrote in the Apologia, 'in spite of my affection for Oxford and Oriel, yet…I had a true devotion to the Blessed Virgin, in whose College I lived, whose Altar I served, and whose Immaculate Purity I had in one of my earliest printed Sermons made much of'. There's the amazing thing: that an Anglican in the early nineteenth century could associate the words 'immaculate' and 'Mary'. He refers to a sermon he preached in 1832, the year before the 'official' start of the Oxford Movement, where he spoke of Mary as the 'Second Eve' and hinted at the Immaculate Conception, though he dared not use such popish terminology. Yet his beliefs were clear: 'what, think you, was the sanctified state of that human nature, of which God formed His sinless Son; knowing as we do, "that which is born of the flesh is flesh", and that "none can bring a clean thing out of an unclean?"'

As a Catholic, Blessed John Henry was more forthright in his views and asked: 'what is there difficult in this doctrine? What is there unnatural? Mary may be called, as it were, a daughter of Eve unfallen.' He wrote elsewhere: 'we do not make her nature different from others. Though, as St Austin says, we do not like to name her in the same breath with mention of sin, yet, certainly she would have been a frail being, like Eve, without the grace of God. A more abundant gift of grace made her what she was from the first. It was not her nature which secured her perseverance, but the excess of grace which hindered Nature acting as Nature ever will act. There is no difference in kind between her and us, though an inconceivable difference of degree. She and we are both simply saved by the grace of Christ.'

Why was Mary preserved from the stain of original sin? Those who come near to God, the source of all goodness and holiness, must be holy themselves. No human being came as near to Him as Mary did. A prophet who acts as His oracle; a mystic who reaches the highest mansion; a priest who consecrates the bread and wine – none of these are as close to God as Our Blessed Lady. As Mother of God she carried the second person of the Trinity in her womb, she became, if you like, a living, walking tabernacle, the new ark of the covenant. And so it was fitting that Mary was prepared in this unique way.

Returning to Oxford's 'Virgin Porch': the statue of St Mary the Virgin remains a discreet but ever maternal presence in the heart of this city, watching no longer the passings of Cavaliers and Roundheads with their pikes and muskets but successive generations of undergraduates, rushing by with their iPods and iPhones. Tonight we turn to her, as patroness of this diocese and patroness of the Oratory. She points us, as ever, towards her Son and reminds us of the primacy of grace, which St Paul calls God's 'free gift to us in the Beloved'. Because without grace, Mary would have been nothing; likewise, whatever our talents, we cannot achieve anything without first acknowledging our total dependence on God. Mary was given the highest fullness of His Kingdom. We too are granted wonderful graces, hour-by-hour – of the same kind but not to the same degree. As we honour the unique privileges for Our Blessed Lady, let us become more aware of this invisible life of grace, without which we are vessels of clay and only that. As we prepare for Christ's coming, let us follow in the footsteps of the Immaculate Virgin – 'for nothing is impossible to God.'

Fr Nicholas Schofield, 8.xii.2010